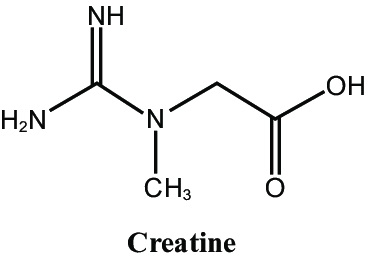

Creatine, a naturally occurring substance found in meat and fish and produced by the human body, is a compound that has garnered significant attention, particularly within the realms of sports nutrition and health supplementation. This article aims to provide an in-depth exploration of creatine, shedding light on its biological processes, applications, potential benefits, and crucial considerations.

Creatine Biochemistry: A Symphony in Cells

Creatine is synthesized in the liver, kidneys, and pancreas, and it also derives from dietary sources, primarily meat and fish. The body converts creatine into creatine phosphate or phosphocreatine, storing it in muscles where it becomes a vital energy source. During intense, short bursts of activity, such as weightlifting or sprinting, phosphocreatine serves as a rapid ATP regenerator, facilitating energy production.

Creatine Supplements: The Appeal and Attraction

Creatine supplements have gained popularity, especially among bodybuilders and competitive athletes, with an estimated annual expenditure of approximately $14 million in the United States. The allure lies in creatine’s potential to increase lean muscle mass and enhance athletic performance, particularly in high-intensity, short-duration sports like weightlifting and high jumping.

However, the response to creatine supplementation varies among individuals. Studies suggest that those with naturally high creatine stores may not experience the same energy-boosting effects. The controversial nature of using creatine for athletic performance is reflected in differing stances, with organizations like the International Olympic Committee prohibiting schools from providing creatine to athletes, though not outright banning its usage.

Creatine and Athletic Performance: A Deeper Dive

While creatine’s positive impact on strength and lean muscle mass during high-intensity, short-duration exercises is supported by preliminary studies, there is ongoing debate regarding its efficacy in endurance exercises. The nuanced relationship between creatine and athletic performance, often studied in laboratory settings, necessitates further exploration to understand the mechanisms driving its effects.

The decision to take creatine depends on various factors. Research indicates that consistent use of creatine, coupled with weightlifting and exercise, is associated with increased muscle growth, especially in individuals aged 18 to 30. However, the available research is insufficient to assert that creatine contributes to muscle development in individuals over the age of 65 or those with muscle-affecting diseases. Therefore, the appropriateness of taking creatine may vary based on individual circumstances and age groups.

Beyond the Gym: Creatine in Health and Disease

Creatine’s influence extends beyond the realm of athletic performance, showing promise in various health conditions:

- Heart Disease: Preliminary studies suggest creatine supplements may lower triglyceride levels and potentially benefit individuals with heart failure, improving exercise capacity and muscle strength.

- Cancer: Early research indicates that creatine may possess anticancer properties, signaling a potential avenue for future investigations.

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Studies suggest that creatine supplementation may increase muscle mass, strength, and overall health status in individuals with COPD, although further research is needed.

- Muscular Dystrophy: While results are mixed, some studies suggest a small improvement in muscle strength with creatine supplementation in individuals with muscular dystrophy.

- Parkinson’s Disease: Creatine has shown promise in improving exercise ability and mood in people with Parkinson’s disease, though caution is advised when combining creatine with caffeine.

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Creatine appears to slow the progression of ALS and enhance patients’ quality of life, showcasing potential therapeutic benefits.

Dietary Sources and Available Forms

Approximately half of the body’s creatine is produced internally, while the rest comes from dietary sources. Wild game, lean red meat, and certain fish are rich in creatine. Creatine supplements come in various forms, including powders, liquids, tablets, capsules, and other preparations.

Dosages, Precautions, and Possible Interactions

Dosages:

While creatine appears generally safe, caution is essential. Sample doses for adults include a loading phase of 5 g of creatine monohydrate four times daily for 2 to 5 days, followed by a maintenance dose of 2 g daily. Creatine absorption may be enhanced when taken with carbohydrates.

Precautions:

Creatine’s potential side effects include weight gain, muscle cramps, stomach upset, and, at high doses, kidney damage. Notably, rhabdomyolysis and sudden kidney failure have been reported in extreme cases.

Interactions:

Creatine may interact with certain medications, including NSAIDs, caffeine, diuretics, cimetidine, drugs affecting the kidneys, and probenecid. Individuals with kidney disease, high blood pressure, or liver disease are advised against creatine use.

Conclusion: Navigating the Creatine Landscape

Creatine’s journey from a naturally occurring compound to a sought-after supplement reflects its diverse roles in both performance enhancement and potential health benefits. While the scientific community continues to unravel its complexities, caution should guide its usage, particularly at higher doses.