Barrett’s esophagus: A patient’s guide

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition in which the tissue lining the esophagus undergoes changes, becoming similar to the tissue lining the intestines. This condition is significant because it can increase the risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma, a type of esophageal cancer. Here’s what you need to know about Barrett’s esophagus, from causes and symptoms to diagnosis and treatment.

What causes Barrett’s esophagus?

The exact cause of Barrett’s esophagus is not fully understood, but it is closely associated with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD is a condition where stomach acid frequently flows back into the tube connecting your mouth and stomach (esophagus). Over time, the acid reflux can cause the cells in the esophagus to become damaged and change.

Symptoms of Barrett’s esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus itself does not cause symptoms. However, many people with Barrett’s esophagus have symptoms associated with GERD, including:

- Frequent heartburn

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Regurgitation of food or liquid

- Chest pain

Patients should manage these symptoms effectively, as ongoing acid reflux can lead to further damage to the esophagus.

Diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed through an endoscopy and biopsy. During an endoscopy, a thin tube with a camera at the end is passed down your throat, allowing the doctor to examine the esophagus. If Barrett’s tissue is suspected, small samples of tissue (biopsy) are taken to be examined in the laboratory for the presence of precancerous cells or dysplasia.

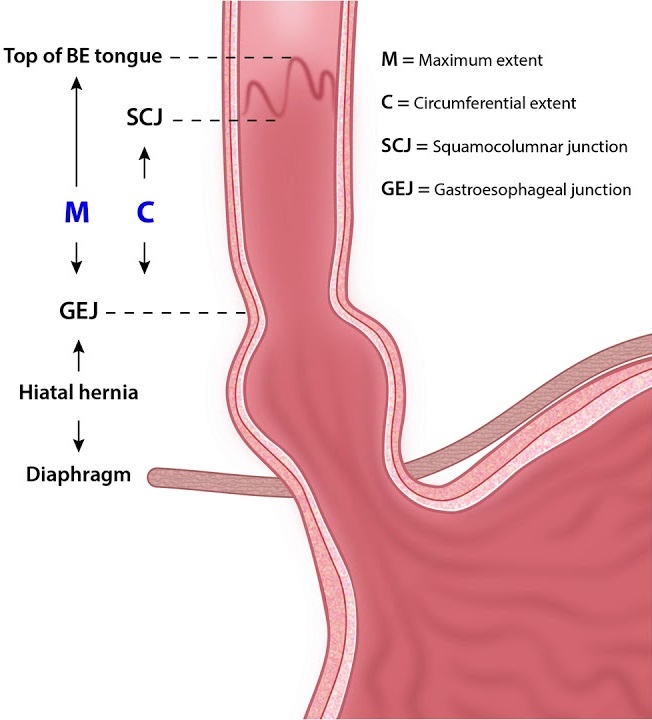

The Prague C & M Criteria provide a systematic and standardized method for endoscopically describing the extent of Barrett’s esophagus. This classification system was developed to offer a clear, reproducible way to report the findings of endoscopy in patients with Barrett’s esophagus, helping in the diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring of the condition. The Prague C & M system focuses on two main dimensions:

1. Circumferential (C) Extent

This refers to the maximum length (in centimeters) of the circumferential Barrett’s esophagus segment observed during endoscopy. It is denoted by a “C” followed by the measurement in centimeters. For example, “C2” indicates a 2 cm circumferential segment of Barrett’s esophagus.

2. Maximum (M) Extent

This denotes the maximum length (in centimeters) from the gastroesophageal junction to the furthest proximal extent of the Barrett’s esophagus, including both the circumferential segment and any tongues or islands of Barrett’s tissue. It is marked as “M” followed by the measurement in centimeters. For instance, “M6” signifies that the maximum extent of Barrett’s esophagus reaches 6 cm from the gastroesophageal junction.

Importance of the Prague C & M Criteria

- Standardization: Before the adoption of the Prague C & M Criteria, there was a significant variation in how the extent of Barrett’s esophagus was described, leading to inconsistencies in reporting and difficulties in comparing study outcomes. This system provides a uniform language for describing the findings.

- Reproducibility: The criteria offer a straightforward and reproducible method that can be easily applied by different practitioners across various settings, enhancing the reliability of diagnosis and monitoring over time.

- Clinical Decision Making: By accurately describing the extent of Barrett’s esophagus, the Prague C & M Criteria help in clinical decision-making, particularly in assessing the risk of progression to dysplasia or adenocarcinoma, planning surveillance intervals, and considering treatment options.

- Research and Surveillance: The standardized reporting facilitated by the Prague C & M Criteria aids in research, allowing for more accurate comparison of data across studies. It also assists in the surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus, enabling the tracking of disease progression or regression over time.

In practice, endoscopists use the Prague C & M Criteria alongside other diagnostic information, such as histopathological findings from biopsies, to make a comprehensive assessment of Barrett’s esophagus. This approach helps in tailoring the management plan to the individual patient’s needs, optimizing outcomes in those with this condition.

Treatment of Barrett’s esophagus

The treatment for Barrett’s esophagus focuses on preventing further damage from acid reflux and monitoring the esophagus for signs of progression towards cancer. Treatment may include:

- Medications: Drugs such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce stomach acid and help heal esophageal damage.

- Lifestyle Changes: Dietary modifications, weight loss, and quitting smoking can help manage GERD symptoms.

- Surveillance Endoscopy: Regular endoscopic examinations help monitor changes in the esophageal cells. The frequency of these exams depends on the presence and severity of dysplasia.

- Endoscopic Treatments: For people with high-grade dysplasia or early esophageal cancer, endoscopic procedures like radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) can remove or destroy the precancerous cells.

Living with Barrett’s esophagus

Being diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus means you will need to be vigilant about managing GERD symptoms and undergoing regular monitoring for signs of progression to cancer. However, with proper management, many people with Barrett’s esophagus live normal, healthy lives.

Factors influencing progression

- Dysplasia Level: The presence and grade of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus tissue are significant predictors of cancer risk. In patients with no dysplasia or low-grade dysplasia, the progression rate to cancer is much lower than in those with high-grade dysplasia.

- Length of Barrett’s Segment: Longer segments of Barrett’s esophagus have been associated with an increased risk of progression to cancer.

- Lifestyle Factors: Smoking, obesity, and dietary factors may also influence the risk of progression.

- Genetic Factors: There may be genetic predispositions that affect an individual’s risk of progression from Barrett’s esophagus to cancer.

Estimated progression rates

- No Dysplasia: For patients with Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia, the estimated risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma is relatively low, around 0.1% to 0.5% per year.

- Low-Grade Dysplasia: In patients with low-grade dysplasia, the progression rate to cancer is estimated to be higher, around 0.6% to 3% per year.

- High-Grade Dysplasia: Patients with high-grade dysplasia have a significantly higher risk of developing esophageal cancer, with annual progression rates estimated to be between 6% and 19%.

Monitoring and management

Given the variable risk of progression, patients with Barrett’s esophagus are typically placed under a surveillance program that involves regular endoscopic exams and biopsies to monitor for dysplasia. The frequency of these exams depends on the presence and grade of dysplasia, ranging from every 3 to 5 years for those without dysplasia to every 3 to 6 months for those with high-grade dysplasia.

Conclusion

If you’ve been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus, work closely with your gastroenterologist to manage GERD symptoms and to adhere to a recommended surveillance program to monitor changes in your esophagus. With effective treatment and regular monitoring, the risks associated with Barrett’s esophagus can be significantly reduced, allowing you to maintain a good quality of life.